This post analyzes that celebratory beauty in the condition of being “unfinished.” It also acknowledges a philosophically rich contemplation. It argues against calling these works failures. Instead, they invite us to refight the essence of “completion.” We reexamine our obsession with perfection. They reveal darker mysteries lying in imperfection.

The Allure of the Unfinished: An Invitation to Wonder

Have you ever gazed at a painting, forming a fascinating wonder? You ponder not only what’s there but also what’s beneath it. There have been more? Most artworks indeed termed “unfinished” would have such bewitching quality compelling them to pose these deep questions.

What Does “Unfinished” Even Mean?

Highly subjective this term-according to culture, even more individual taste. It is this approach, looking upon such works with more sensitivity, thus perhaps speculating about the artist’s intention, that leads to a data search on what creativity controls. Offers an intimate peek into the creative process-how the artist thinks and techniques are layered.

Importantly, still, “finished” would hardly be a description as far as these works go. Is technical perfection like every detail has been perfectly rendered? Or does it refer to something greater, like the application of one’s artistic vision? That’s the moment when the artist feels they have reached their goal. Dramatic external forces, even the death of the artist, can leave a work unfinished. These works compel us to rethink entire art understandings and start a vital discussion about artistic process and subjective beauty. Surprisingly, they can be worth a fortune in their incomplete state.

Ultimately, these works remind us that art isn’t just about perfection; it’s about exploring, expressing, and human creativity without bounds.

Key Takeaway: ‘Unfinished’ art is not a flaw. It is a great invitation to investigate the making of creativity. It explores the subjectivity of completion. The piece often remains unmoving as it reveals truths much deeper than ‘better-spent’ works.

Defining the Indefinable: When is Something Nonetheless “Finished” in Art?

Let’s start with this question: What does it take to perfect an artwork?

The most enduring controversy on whether one can say a work of art is finished is historical. Being impeccable. This was what artists like Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci were all about during the Renaissance. Every line, every curve, had to exemplify harmony and balance.

Jump to now, and describing “finished” has changed dramatically. Most contemporary artists now consider a work as part of a process. It is not seen as an end they aim to achieve.

In current modernity, the world of art thrives on process rather than product. The creation process is equally valued by the final image. As Pablo Picasso famously declared, “Art is never finished, only abandoned.” This highlights the perfection fallacy. It invites us to consider what unfinished art truly is. These are not failures. They are breathing works still developing in the minds of the beholders.

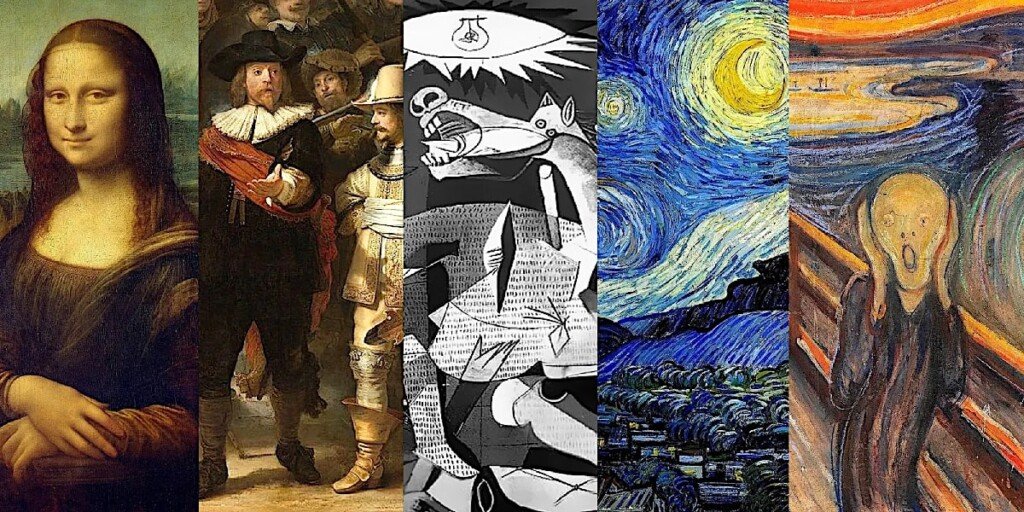

Five Unfinished Masterpieces: An Insight into the Artist’s Soul

Five of the most well-known paintings can’t all officially be called completed. Now, we will study those pieces. This very quality of incompleteness has given all of them a sense of timelessness. Each of these pieces tells stories of artistic genius. They also reveal struggles, doubts, and the profound complexities of human life.

Da Vinci obsessively pursued unattainable visions. Edvard Munch experienced psychological tortures. These unfinished works show us the emotional depths of great art. Let’s enter the workshops of these creative minds to discover the secret lives of their unfinished masterpieces.

Mona Lisa — Leonardo da Vinci (1503–1519)

What if the world’s most enigmatic smile isn’t a mark of perfection? What if it is the opposite, a whisper of Leonardo’s lifelong struggle with ‘completion’? The ‘Mona Lisa’ by Leonardo da Vinci stands in stature with the most celebrated works of art. It is also one of the most debated in history. Yet, this masterpiece never to him felt really ‘finished’.

Infrared scans were performed by the staff of the Louvre Museum. These scans reveal that there are three different draft layers underneath the surface of the painting. This suggests that da Vinci often returned to the landscape after finishing the figure. He hardly ever achieved the satisfaction he sought for it. In his notes, he made the pained remark, ‘figure done, landscape not.’ It’s said he wished to change the veil around her neck even in the last hours of his life.

The mystery of the Mona Lisa is due to unexplained reasons. Her enigmatic smile and dreamlike setting are not a conscious symbol of perfection. Instead, they show the artist’s struggle to reconcile his great vision with reality. Learn more about the scientific analysis of the Mona Lisa.

The Night Watch — Rembrandt (1642)

Another stimulating example of an “unfinished” piece, defined by external intervention, is Rembrandt’s “The Night Watch”. The dramatization and theater in many of his works are quite spectacular. This is especially true for a work like it that was given a fullness of motion and light. Oddly enough, the picture you behold today is not the one Rembrandt initially painted. The current configuration is not his original work.

Its earlier title was “Militia Company Under the Leadership of Captain Frans Banning Cocq.” The painting was severely cut in 1715 to take a smaller wall. Over time, the slash of the canvas erased six figures as well as 16 more pieces beyond that. In 2021, though, such portions were digitally prefabricated really thanks to AI technologies. Hidden would-be signatures from Rembrandt were even found within such rehabilitated areas.

To realize your utmost work in life was physically cut apart. After ages, it was returned by artificial intelligence. This painting became the strong emblem of impermanence and resilience. It also symbolizes the enduring nature of art in the technological resurrection process. Explore the digital reconstruction project by Rijksmuseum.

Guernica — Pablo Picasso (1937)

What if, in reality, silence speaks louder than all the censored symbols in a charged antiwar message? Very few paintings shriek like Picasso’s Guernica. It stands as an unambiguous statement against the war. It is often acclaimed for being one of the most powerful political works ever made. Yet, the process of its creation was heavily conditioned by external damages, censorship, and fear.

First of all, the painting would carry a caricature of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco. There would also be a ragged Nazi flag riddled with swastikas. Later, though, these overt elements were struck out by the pressure of political allies and institutions. Instead, he insidiously slipped in a hammer and sickle as a veiled reference to communism. Picasso says he intends to return to the piece to treat it properly in 30 years. Sadly, he never lived long enough.

Guernica speaks volumes. Sometimes, what has been excluded due to political or social forces speaks much more than what is argued. The narrative would stay open for reinterpretation. Read more about the political context of Guernica.

The Starry Night — Vincent van Gogh (1889)

Picture an artist whose most renowned piece, admired by millions, was simply regarded as a failure in his own eyes. If there is a picture that carries universal fame, it is Van Gogh’s Starry Night. This fame will continue. Yet, the painter doubted it. To his beloved brother Theo, he wrote that the painting did not come off satisfactorily. He discarded it as overly abstract and unnatural.

Even more shocking was something one learned from X-ray examination. X-rays revealed a village that Van Gogh unveiled below the swirling sky. This village was on that canvas. He erased and repainted it many times thereafter. Such persistent revision reflects the turbulence inside him — the acutely felt clash between bursting creativity and looming insanity. The very drive to keep on keeping on and changing was his most virtuous strength. Redoing was equally his greatest undoing. This was an emotional truth that never really is “finished.”

Picture Vincent van Gogh as an impassioned artist, never quite attaining fame during his prototypes. Only one painting was sold while Vincent van Gogh was alive. Such immense obscurity shows the trials many artists endure. This is especially true for artists whose creativity defies the mainstream. Van Gogh had a very distinct style in the mainstream art of his time he hardly found sympathizers-. His strokes were coarse, with bold colors, and, in fact, too radical.

Theo played a pivotal role in the preservation and promotion of Vincent’s work. Theo’s unabated support was among the lasting legacies of Van Gogh. He believed in his brother’s extraordinary talent and promoted his work with great energy. Had Theo not played such a vital role, Van Gogh’s works have been lost without a trace. Today, The Starry Night, one of Vincent van Gogh’s most renowned pieces, is valued at above a hundred million dollars.

Such a valuation stands as irrefutable proof of Van Gogh’s immensely greater posthumous fame than he ever enjoyed. Vividly tells of the haunting influence that Van Gogh continues to exercise In the world of art. His story motivates an innumerable number of artists to keep the faith. Their success lies in their ability to fight through and hold on to their unique vision. It is a vision that never quite feels truly “finished” in the artist’s mind. Discover more about the hidden layers in The Starry Night via MoMA.

The Scream — Edvard Munch (1893)

What if that howl seemed to shake the very foundations of art history? It was neither a solitary scream nor an isolated confession. Instead, it was the echo of an unending quest: an artist’s quest for emotional truth.

Edvard Munch did not paint ‘The Scream’ once; he painted it four times. All are quite distinct from each other but punctuated by some deep existential pain. In one corner of one frame, he scrawled with a pencil. He wrote: Kun kun en galning kan ha malt dette-Only a mad have drawn this.

In his 1904 letter, he confessed: “I never quite got the sky-red right.” He was still not satisfied. His vehemently passionate pursuit of what he called emotional truth prompted him constantly to re-envision this image. “The Scream” underwent a metamorphosis. It became more than just a painting. It turned into a feeling that wouldn’t shut up. There was an imploring for the artist to totally perfect his work before considering it finished. See the Munch Museum’s detailed exploration of The Scream.

The emotional profundity of Munch is fascinating. This, coupled with that straining in art towards completing and yet not ceasing, captivates you. You also stand to gain from another of his haunting works. I earlier rendered this artist’s paradox of love that tenderly nurtured but offered pain through my earlier article. “Encountering ‘Love and Pain’ by Edvard Munch,” I referred to how he does not cease searching for emotional truth. He does this through unfinished echoes but finds mystery in one of his haunting works.

Encountering “Love and Pain” by Edvard Munch

Discover the intense emotions depicted in Edvard Munch’s “Love and Pain”, also known as The Vampire. This dense masterpiece is rich in emotion, symbolism and mystery. It invites contemplation of the duality of love, and of the way it can be both beautiful and destructive.

New Perspectives on the Unfinished: Beyond the Old Masters

There were other creative persons beyond the old masters who grappled with the idea of completion. Living legend David Hockney remembers working and reworking his famous Pool with Two Figures over 1,500 times. He still considered it not finished in his mind.

Yayoi Kusama states that she has infinite mirror rooms. She is never happy with her signature dots. There have to be more of them. This realization shows that the boundary between finished and unfinished is more nuanced than we think. This nuance is one of the very things keeping the art form alive and evolving.

Why Is Your Brain Craving Unfinished Artworks: The Zeigarnik Effect and Aesthetic Incompleteness

So why do we obsess over cliffhangers, or replay scenarios in our minds? There is a fascinating psychological phenomenon. It explains our ardent attraction toward unfinished artwork. A deeply seated psychological reason underlies the human obsession with unfinished artwork.

The neuroscience of partially completed images activates the predictive circuitry of your brain. These are the same areas that compel you to “work out” that cliffhanger you just saw on Netflix. They also make you imagine a better ending for that book you just read. A 2017 study published in Nature Communications showed something fascinating. When spectators are presented with fragmented works of art, their brains generate simple emergent simulations. This leads to a profound sense of ownership over the interpretation.

So potent is the Zeigarnik effect. Unfinished tasks linger in the mind longer than those that are finished, like that unanswered text message gnawing at you. Unfinished art persistently lingers in your memory. Ever sat there re-watching a movie, mentally writing a different ending? That same obsessive thought draws someone to a half-painted Mona Lisa or a hazy Munch drawing, making it utterly alive.

But there is a sinister side. Giorgio Vasari, a Renaissance art historian, hinted that artists like Leonardo left their works half-finished because they feared imperfection. But this very quality is taken today as a window to genius. This perspective has led to the modern view of ‘aesthetic incompleteness’. The more an artwork solicits our full engagement to finish it in our minds, the more we praise it. In an era of algorithm-fed content, unfinished artworks invite active vision-seeking. This is a rare and profound act of protest. It stands against passive consumption.

Unfinished does not mean incomplete. It’s a dialogue that stretches across the centuries, with each person contributing verse to its unfolding story.

A Statistical Glimpse: The Market’s Embrace of Process

In reality, it is the statistics and insights that make their understanding more. The prospective market value of the art market globally in 2022 at $67.8 billion simply shows how hugely art has escalated in valuation and its rising importance as an international industry. The art market is continuously evolving with the appearance of new artists and new styles.

Francis Bacon, one of the most famous artists, says that the “job of art is always to deepen the mystery.” This statement really attracted me to art. It reminds us again and again that art is not always about giving answers but really opening new perceptions.

In the report by Art Basel and UBS on the Global Art Market Report 2023, total sales value appreciated. This happened even though there was a sales decline of 12% in 2022. Meanwhile, deal values rose by 3%. This is more than a market fluctuation; it reveals an interesting shift.

Collectors and the audience are increasingly valuing a broader spectrum of art. This includes not just the polished masterpieces but also works that question traditional notions of completion and perfection. This aligns perfectly with the allure of the “unfinished.” This shows that there is increased interest in a variety of artists from both established and emergent ones.

Drawing Parallels Across Disciplines: Incompletion Beyond Art

The idea of “unfinished” has resonance much larger than art. For psychology, for example, the process of self-discovery is not done. Personal development is an evolving sketch rather than a finished portrait. Self-understanding is like unfinished art. It is a continuous process of becoming. The human condition is riddled with unanswered questions and ongoing revisions.

In history, events constantly form new pictures. They reshuffle our ideas about contemporary life. Similarly, ambiguity seems to flood into every fixed idea of perfection. Historical narratives keep changing and evolving as more evidence comes forth.

Even in science, theories are never truly finished. Even if they were framed as such, they would not be whole boxes for discovery. Understanding itself is an ongoing evolution, not a fixed destination.

Our fascination with incompletion shows our curious nature. We are forever imagining the next or what else will be.

The ‘unfinished’ concept mirrors human experience beyond art. It reflects how self-discovery and historical narratives are dynamic. Even scientific theories are evolving processes rather than fixed, ‘finished’ states.

In the Bosom of Infinity: Why Unattempted Art Speaks to the Commonality of All Human Beings

These works lead to a profound realization. Art oftentimes becomes powerful in its unresolved situations. Its enticing “what ifs” evoke sweet dreams. The greatest works do not end with sighs from the artists. Instead, they are the few that suggest: “I have gone further.”

According to author Susan Sontag, “Art is not about answers-it is about better questions.” These five artistic masterpieces remind us that creation is more of a process than any final product. Maybe, stronger art tends to be the art that can hardly stop evolving.

Is anything ever really done about art, anyway? This is also what makes art immortal. That something is the hand of an artist, a discerning viewer, or indeed the very mighty forces of science. You say, reading a poem, you don’t expect the poet to tell what that poem is about. You create your own meaning by yourself.

Art is like an unfinished work. It strongly calls us to action. We must finish it with our thoughts, emotions, and life experiences.

In Completing the Unfinished by Technology

Today, the unfinished comes under the new light of revolutionary development in 3D modeling and another completion of interpretation. Michelangelo’s unfinished sculptures, the “Prigioni,” have found reflection through holographic imaging. Through Google Arts and Culture, Gustav Klimt’s destroyed Faculty Paintings were practically brought to life.

Projects like these expound on how technology can bridge between the artist’s intentions in time. Technology overcomes the limitations imposed by their time. This approach engages new ways of speaking about these never-finished works. Explore Google Arts & Culture’s restoration projects.

Final Reflections: Perfection Unfinished

This is a question worth asking yourself. Consider it the next time you stand in front of what passes for a finished masterpiece. Is the artist ever truly finished? Or is this just one pause in an ever-unfolding dialogue with creativity?

Ultimately, ‘unfinished’ as an idea is not a flaw. It is an invitation to see beyond-the-canvas creation. It refers to raw humanity. It challenges us to question what is done in a world obsessed with finitude. When we experience these compelling masterpieces, we see the inkling layers of stroked Mona Lisa. We notice the shadowy forms of The Night Watch. We notice the erased signs of Guernica and the tumultuous revisions of Van Gogh. We hear the echoing screams of Munch. It will not just be art, but also the human condition itself in its journey of becoming. This is a journey of constant becoming.

It is precisely imperfect staggering and lost images that stir in us. Erased symbols, internal struggles, and ceaseless screams also point to something larger-than-the-human condition in art and life. Unfinished isn’t made imperfect; more often than not, it is without end. That is the secret behind magic in art being eternal-its never truly finished.