Introduction: Why This Portrait Matters

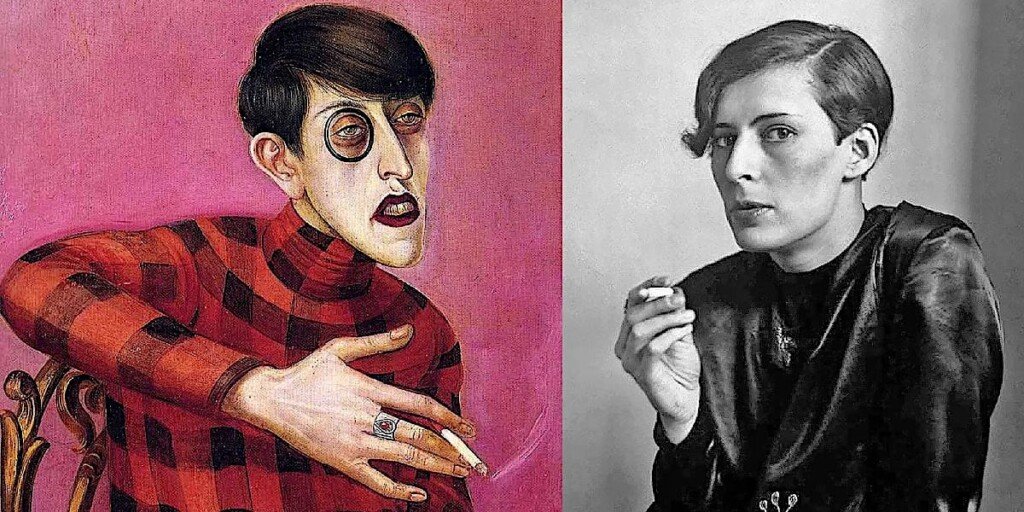

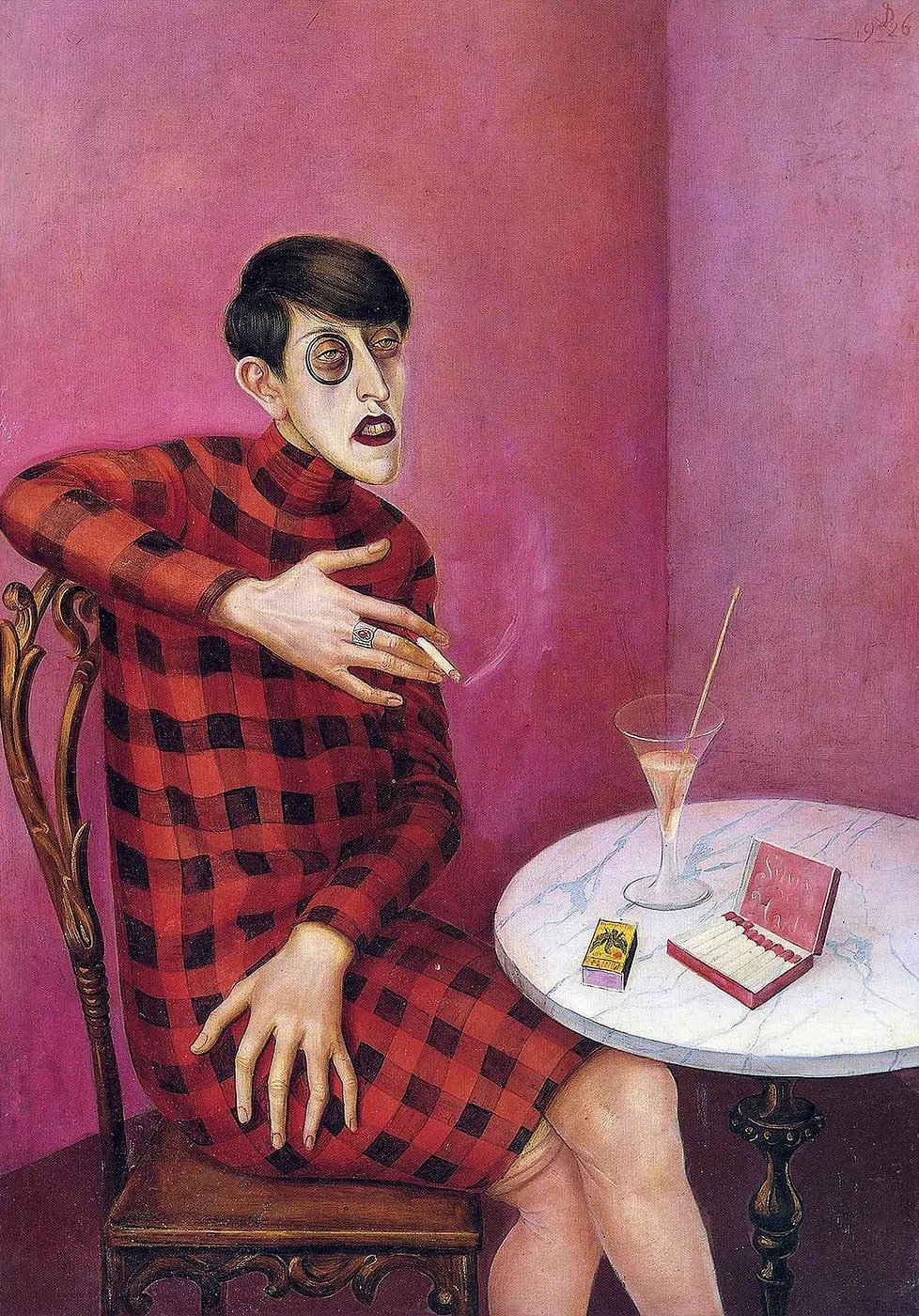

Here I welcome one of the first entries in my new art series: A Personal Commentary. Throughout these reflections, I will try to dump some insights about artworks that have really touched me. These insights come not only on the levels of vision and intellect but also emotionally. I start with a painting. Its image has captivated my imagination for a long time. The painting is Otto Dix’s Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden (1926). It is more than a portrait; it is a historical document, a cultural critique, an artistic assertion. At the center is a woman. She epitomizes a cataclysmic change in the image and identity of women in the modern world.

The Woman Behind the Portrait: Sylvia von Harden

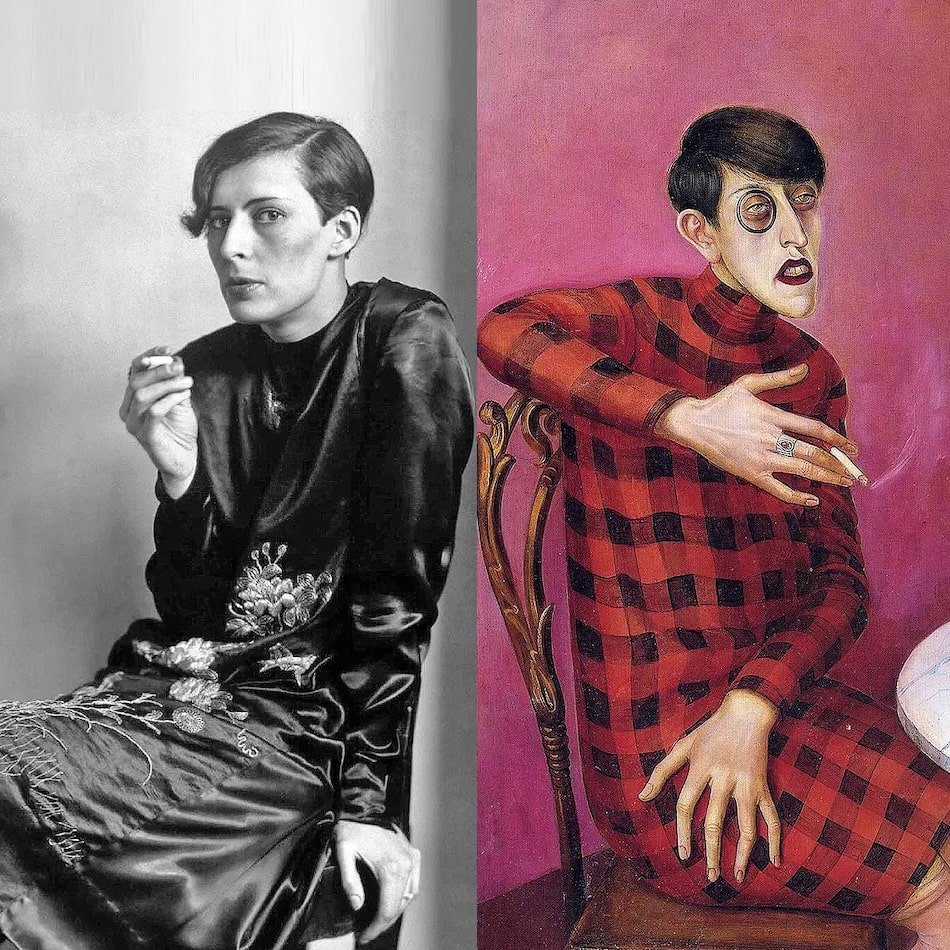

Born after 1894 in Hamburg, Sylvia von Halle was a poet. She was also a journalist and a cultural critic. She left her mark on Weimar Berlin. To ennoble her pretensions even further, she chose the pseudonym “von Harden.” In journals like Das Junge Deutschland and Die Rote Erde, she provided sharp commentary. She also wrote poetry about the complexity of her times. Her domestic life was as unconventional as her professional one. She lived with fellow writer Ferdinand Hardekopf. She bore a child out of wedlock. This was a daring decision for any woman in the 1920s.

More than a writer, von Harden became a symbol of the Neue Frau, or “New Woman.” She was educated and independent. She was oriented toward a career and never hesitated to clash with society’s norms. Dix chose to immortalize her, not for her conspicuous lack of beauty according to classical standards. He did so because she was the walking embodiment of the cultural rupture of the age.

A Modern Identity Measured: Otto Dix’s Vision

In Dix’s painting of 1926, von Harden comfortably sits with crossed feet at a small cafe table. She wears checkered red and black, has a bob-cropped hairdo, sports a monocle, and holds a cigarette. Her expression is almost indifferent, confident. She does not plead for her viewing; she dominates the space.

Dix was an expert in the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). This was a German movement that laid aside romantic idealism. It embraced stark realism and psychological depth. In von Harden, he realized not merely a muse, but a fleshly incarnation in time. Her androgynous physiognomy, intellectual fervor, and seductive air embodied the style of a changing society.

Symbolism in Detail: Reading the Portrait Closely

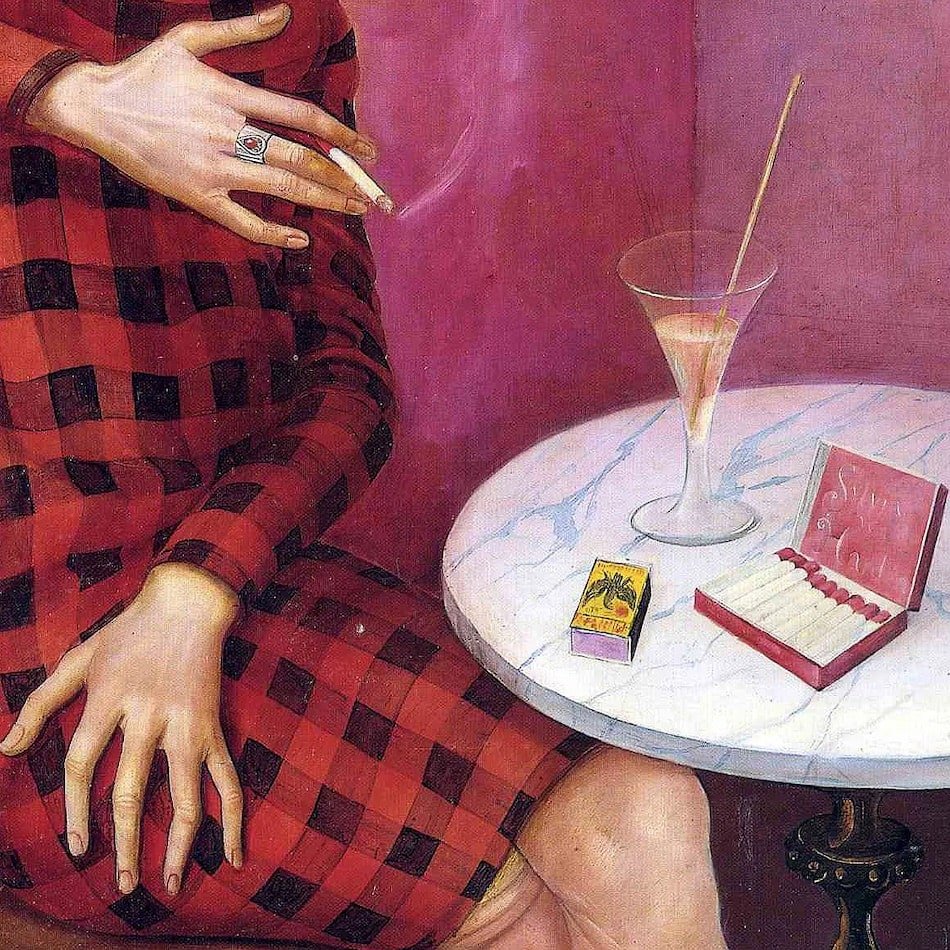

Each part in the painting tells a unique story:

- The café setting places her in the bohemian heart of 1920s Berlin — the intellectual, the liberated, and the commons.

- The cigarette and cocktail are more than props; they symbolize defiance, autonomy, and leisure in a male-dominated world.

- The monocle is usually a masculine accessory. It speaks of scrutiny. It also represents intellect and control. She is both the observer and the observed.

Dix is not flattering von Harden in his portrayal of her “imperfections”; this simply makes her even more powerful. He accentuates her long face, angular features, and rigid pose. Most importantly, such lack of beautification is precisely the point. The portrait declares a new womanhood. It is characterized by character, wit, and agency.

A Collaborative Spirit: The Artist and the Muse

Theirs was a partnership far from passive. Von Harden later recalled with wry humor Dix telling her, “I must paint you! I simply must! You are representative of an entire epoch.” To this, she ironically referred to the crookedness of her nose. She also mentioned the thinness of her lips. Eventually, she accepted.

Von Harden certainly understood that she was thereby being made an icon: she leaned into it. She was no shrinking flower before that idea; she helped to build it.

An Era: The Weimar Republic and the New Woman

They called the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) an era of paradoxes: politically unstable and artistically explosive. It was in this context that the New Woman emerged in reality and as a contested ideal. Women were coming to work and voting. They were wearing pants and being in cafés unaccompanied. Yet, they were also being caricatured, criticized, and constrained by the backlash.

This painting is not idealizing the New Woman; it is interrogating her. It asks us: what happens when a woman claims space, not for decoration but as discourse? What does it mean to embrace individuality when it will get her branded as difficult and misunderstood?

From Berlin to Paris: The Afterlife of the Painting

Today, Dix’s Portrait of Sylvia von Harden hangs in the Musée National d’Art Moderne at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. After decades its conception, it still retains that inquisitiveness, admiration, and contestation. Why? Because it refuses to be simplified. A portrait not just of a woman; a mirror not just to a person but to a society in transition.

It speaks to an age. Discourses on gender identity, freedom of expression, and social expectation are more pressing than ever.

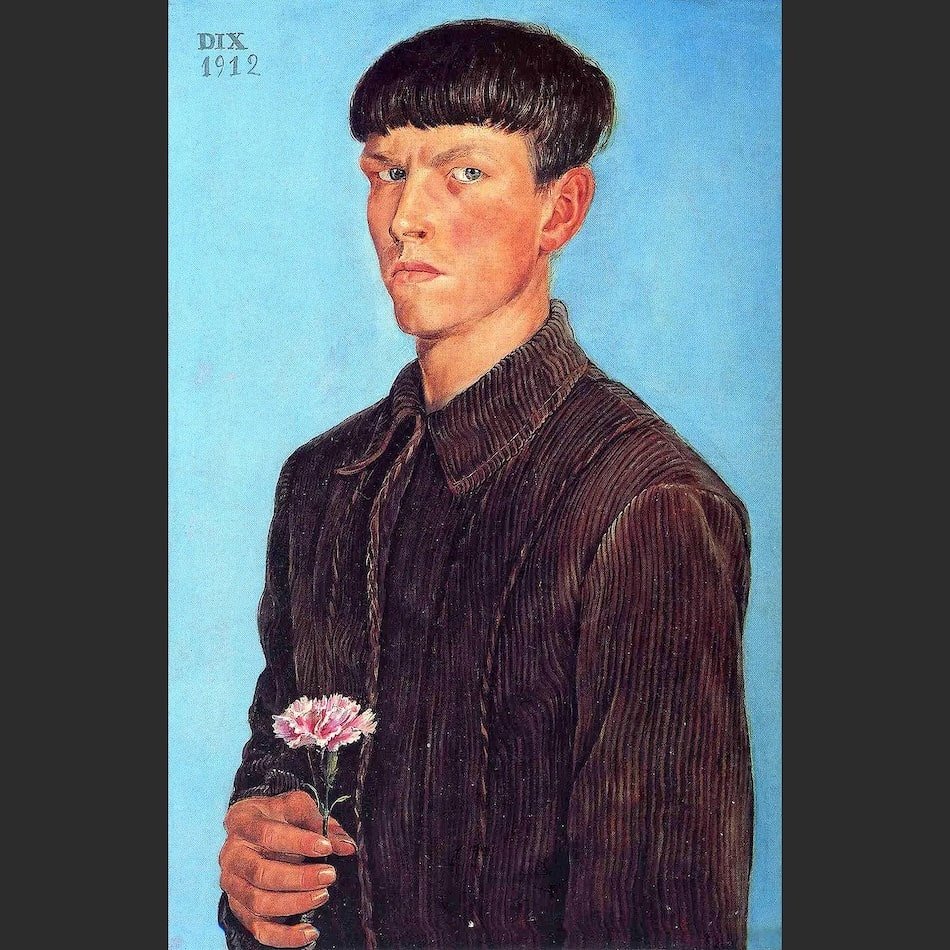

Otto Dix: An Artist Forged by History

An investigation of this kind can’t be thorough without an understanding of Dix’s history. He was born in 1891. He served in World War I. Later, he recorded the horrors of the war in his brutally honest drawings and paintings. He again fought in World War II and was branded “degenerate” by the Nazis. This art is full of trauma, contradictions, and resilience of 20th-century Europe.

That legacy adds even more weight to his portrait of von Harden. This isn’t only modern womanhood. It’s about what it means to be seen. It’s about resisting. It’s about asserting o

Why This Portrait Still Speaks to Us

In the end, the Portrait of journalist Sylvia von Harden only survives for a compelling reason. It speaks a truth we are still fighting: the right to define oneself. Sylvia’s posture, her silhouette, her gaze-a full authorship-an interpretation underway. She is not waiting; she already knows who she is.

People who seek illumination of the human condition in fine art will find value here. This painting is a bold and richly textured example. It reminds us that power does not always roar. Sometimes it just sits coolly at the café table, monocle in place, daring you to look deeper.

Let’s Talk Sylvia: What Does She Say to You?

Now, I’d love to hear your thoughts. Looking at Sylvia von Harden with the eyes of Dix: what do you see? Does that portrait resonate with notions of identity, rebellion, or creative expression?

Feel free to post your interpretation in the comments below. Let’s keep this dialogue going — after all, art is a conversation across time.

Previously in the Series

If you missed it, my last commentary featured the emotionally charged painting by Edvard Munch titled Love and Pain.

Enjoy reading, and thank you for joining this journey through art, history, and self-expression.

Written by Discoverer of ART

Editor, curator, publisher

Twitter (X) – @DiscovererOfArt